By Jonathan Puddick (JP) and Georgia Thomson-Laing

During 2022, the Lakes380 team will be out sharing their passion for lake science and lake ecology with schools in the Nelson region. Because lake restoration is a multi-generational journey, we believe that our best hope for protecting the health of our precious lakes is to get our tamariki passionate about them. We have over 3,800 lakes in Aotearoa-NZ, but kiwis know about relatively few of them; Lake Taupo and Wanaka, maybe Lake Rotorua. Part of this is because many of our lakes are hard to access. A geographic assessment indicated that 28% of Aotearoa-NZ’s lakes are legally impractical to access (they’re located on private land) and 40% are moderate to very difficult to access (they’re in rugged terrain where you might need to tramp for several days or take a helicopter ride to visit them; check out the Connecting New Zealanders to Lakes StoryMap for more information). This has led to a loss of connection to many of our lakes and a loss of connection means that some lakes aren’t getting the attention that they require. StatsNZ modelling indicates that 46% of our lakes have poor or very poor water quality, meaning that they have higher nutrient concentrations, higher levels of algae/cyanobacteria and lower water clarity (visibility). Ultimately this results in the lake not being able to support its natural level of biodiversity; there are less native fish and insects, less water plants (macrophytes) growing on the bottom of the lake, kākahi (freshwater mussels) aren’t as abundant. We hope that teaching people about lake health and talking about the beautiful lakes that we have here in Aotearoa-NZ will move people to reconnect with their lakes, to visit one on their next holiday, and to take an interest in the current state of our lakes and how we can turn that around before it’s too late.

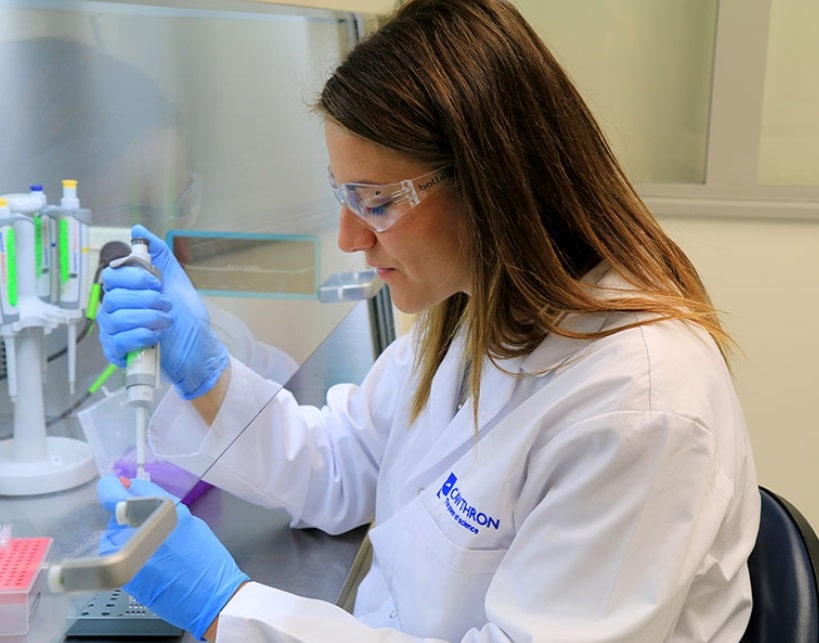

More used to adventures out in the field sampling lakes, our team are excited by this next adventure of interacting with excited and energetic children. To teach the students about our lake ecology work and to get them thinking about what lakes used to be like before humans arrived in Aotearoa-NZ, the team take them through three activities. They extract DNA from a banana to learn about how DNA is everywhere and get some hands-on practical lab experience, they go fishing for environmental-DNA to learn about how we can study what creatures are living in a lake, and they dig through a simulated lake sediment core unearthing clues that tell them the history of that lake and what had happened to it over the past 1,000 years!

Extracting DNA from a banana provides us a way to get hands-on with modern lake science and begin to understand that all living things contain DNA and that we can extract it out of samples. Normally we would be extracting DNA from lake sediment samples, but extracting it from a banana means that we can get enough DNA that you can actually see it. The activity involves squishing and squashing the banana with water, salt and soap to release the DNA, filtering the banana chunks out, adding ethanol (alcohol) to make the DNA appear and, voila, we have banana DNA!!

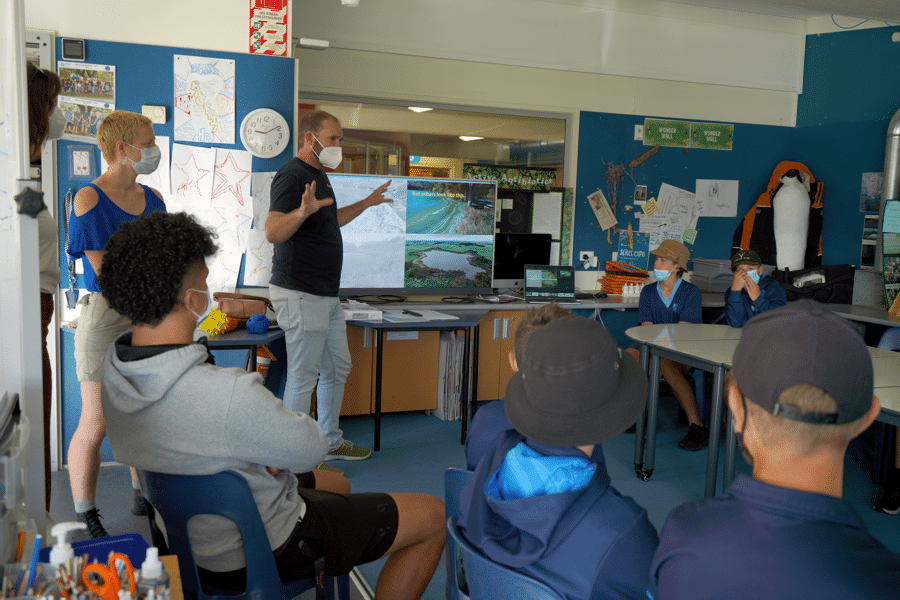

Environmental-DNA (aka eDNA) has been a huge game-changer for lake science. Because all living organisms (fish, microbes, algae) have DNA and shed it, we can use that to understand what is living in or around a lake. We can go to a lake, collect a water or sediment sample, extract the DNA and by analysing the DNA code we can figure out what’s living in the lake and how abundant they are. Our fun activity ‘Fishing for eDNA’ introduces this concept to school students and helps them understand how we can apply this powerful molecular tool. Students get to ‘fish’ eDNA sequences out of our simulated lake and match these to DNA sequences for different animals, plants and even algae to figure out what lives in this lake. We then record the amount of DNA we have collected for each organism and discuss what we might expect this lake to look like and why.

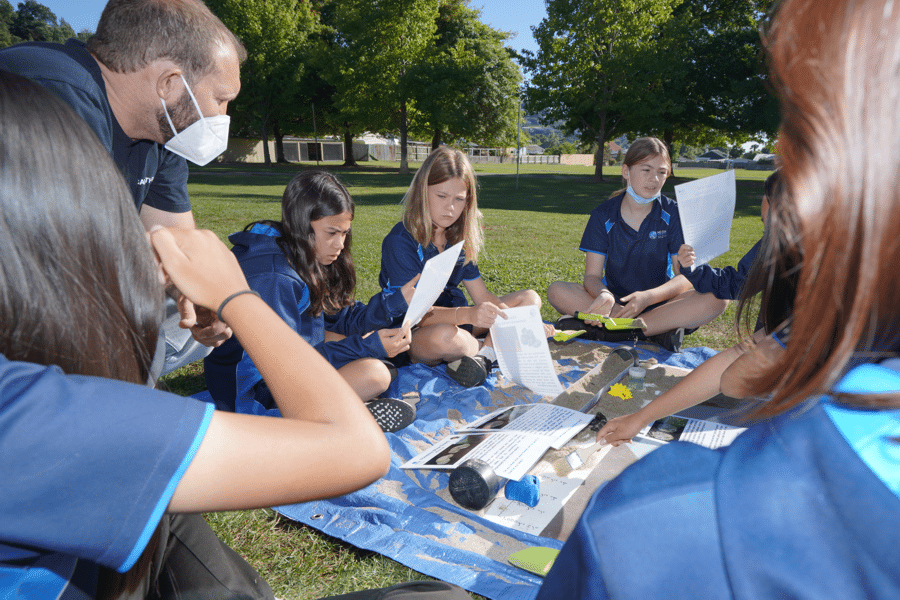

In Lakes380, one of our big aims is to understand the history of lakes in Aotearoa-NZ and tell their stories. To do that we collect ‘sediment cores’ from lakes by banging a plastic tube into the mud at the bottom of the lake. These 2-m long cores contain 1,000 years of lake history as sediment at the bottom of the lake progressively builds up year after year along with clues that tell us what was happening around the lake. These clues might be pollen produced by plants growing around the lake, pigments produced by algae growing in the lake or charcoal that appears when forests are burnt down. These clues tell us what’s been happening around a lake over the past millennium and help us to understand what has led to the lake being in its current state. To simulate this with the students, we bury clues in a sediment core and get them to dig them out (just like we do in the lab). Clues from the top of the core were from recent times and clues from the bottom of the core were from 1,000 years ago. We normally need microscopes and fancy instruments to see the clues in a sediment core, so we provide the students with 3D printed pollen and containers of algae instead. By matching the shape of the pollen with reference cards the students can figure out what the area surrounding the lake used to look like compared to today, and when those changes occurred. Did the lake used to be surrounded by native ferns? Why would we find charcoal in the core? Did we find any pine tree pollen and when would this suggest forestry started? Were there always trees around the lake or can we only find pollen from grasses and dandelions? When did algae start to grow in the lake? This helps the students to develop a picture of what lakes in Aotearoa-NZ used to look like compared to the modern-day image they have from their lived experience.

Together, these activities get our tamariki thinking about what lives in lakes, what lakes used to look like before humans arrived, what they value about lakes, and how we can work together to improve the health of our lakes. At the same time, students get to see that science isn’t all about standing in a lab and mixing solutions together, and that the stereotypical image of what a scientist looks like isn’t necessarily the case nowadays.

A big thanks to the students at Nelson Intermediate School who feature in the photos included in this blog, the Ministry of Inspiration for teaming up with us to deliver this programme and the Cawthron Institute Trust Board for sponsoring this science outreach initiative.