– Shana Dooley, Cawthron Institute Summer Scholar

This summer I joined the Cawthron Institute and Lakes380 team to explore public access to New Zealand’s lakes using GIS (Geographic Information System) analysis.

For the analysis, I created a new lakes dataset, based on an existing dataset from Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) and additional data from the Department of Conservation, NZ Walking Access Commission, Environment Canterbury, and Fish and Game New Zealand. As some Lakes380 lakes were not part of the initial dataset (notably lakes in the Chatham Islands), I had to input them manually.

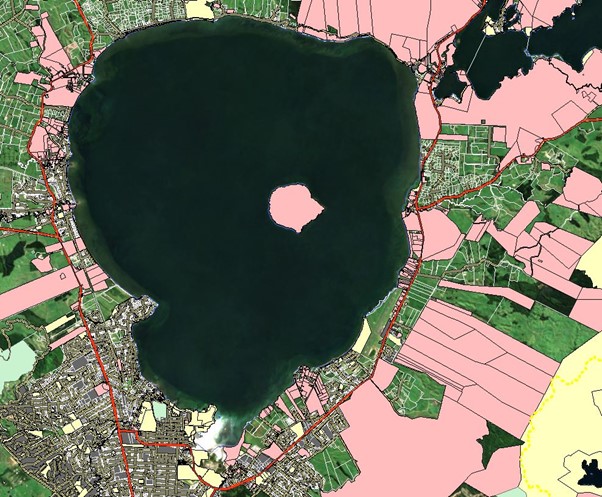

I imported the Lakes380 points into ArcMap and created a new dataset by selecting by location from the altered lakes dataset. I then re-projected and brought 16 additional datasets into a new geodatabase, including public lands, trails, and easements, roads, property titles, Maori land blocks, cities, and satellite and topographic imagery.

Initially, I had envisioned using GIS spatial tools extensively for my analysis, but it quickly became apparent that using automated tools to determine access and ownership was complicated. Small inaccuracies in parcel boundaries could suggest accessways that don’t exist in reality, while the ‘on the ground’ practicalities of accessing lakes are not indicated by map layers. Therefore, I ended up analysing each lake individually in ArcMap by looking at how layers combined to determine public access. Each lake was also “ground-truthed” to verify access, using Google Street View and internet searches.

I found that some lakes had straightforward access points with signage from a road, like Lake Taharoa in Northland.

Yet, public access was complicated or difficult to determine for many lakes. Lakebeds were under varying ownership and many lakes have multiple types of land ownership surrounding the lake. Often, what appeared to be an access point was different on-the-ground.

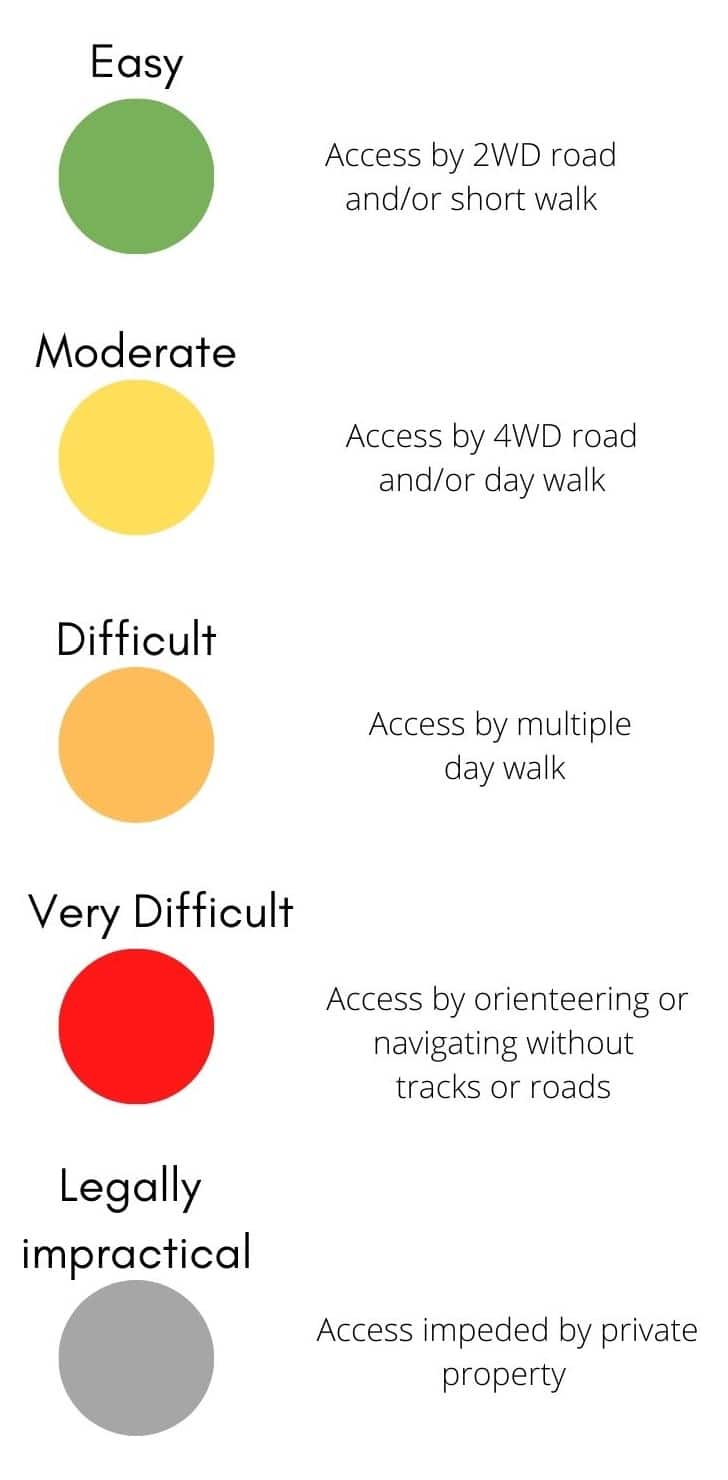

For each lake, I assessed lakebed ownership, land ownership around the lake, recreational use, and method of access and added this information to the database. I then classified each lake according to an overall category of easy, moderate, difficult, or very difficult access, based on the primary access method – walking, a sealed road, 4WD track, or navigating. I added a fifth category of ‘legally impractical’ to identify those lakes where public access is impeded by private land.

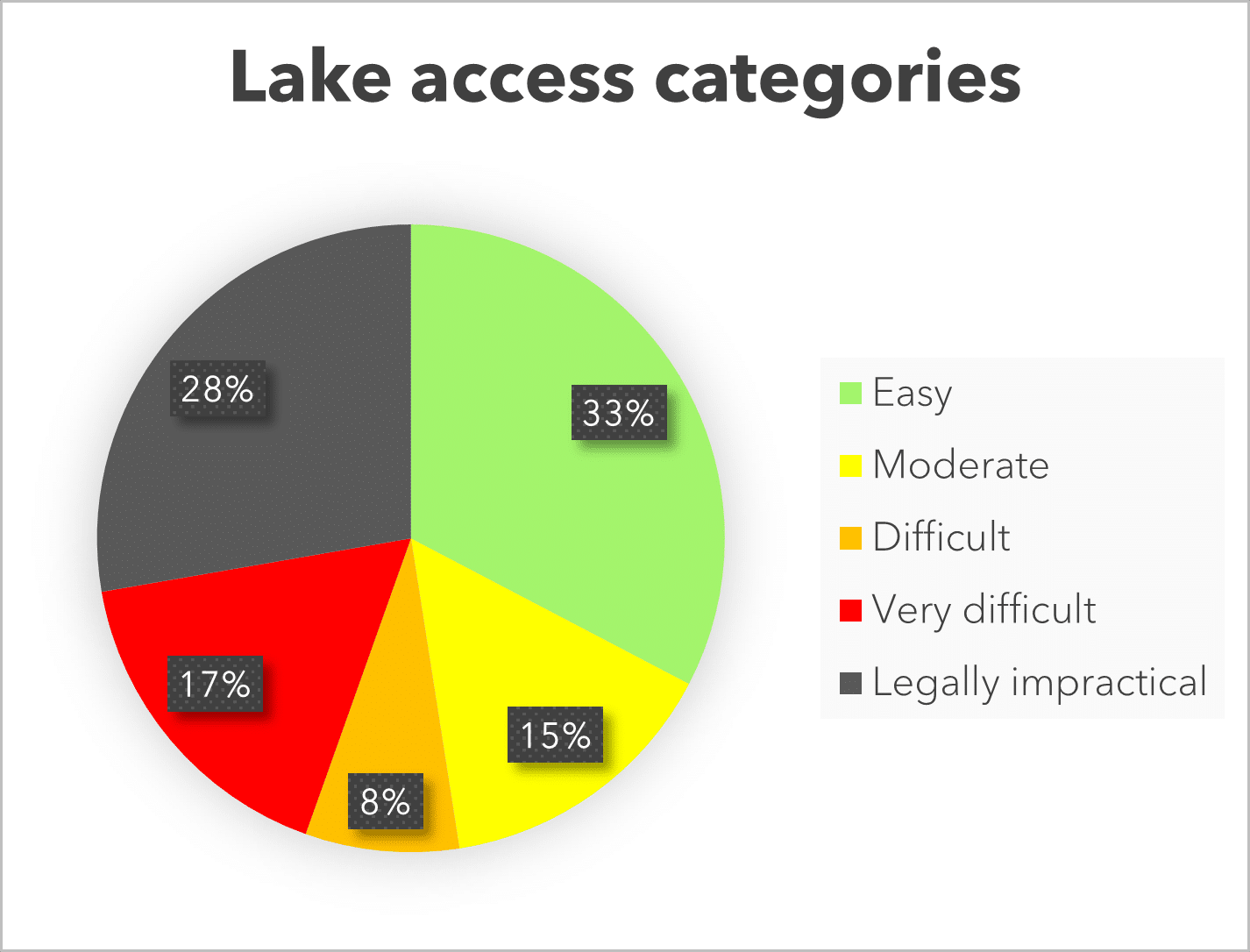

Overall, my analysis shows that 33% of lakes are ‘easy’ for members of the public to access. However, 28% are legally impractical to access, meaning that private property is a barrier to public access. Many lakes – 40% – are moderate to very difficult to access, requiring specialised vehicles and/or a higher level of fitness and outdoor skills. These results indicate that there are barriers to public access for many New Zealand lakes.

Some of these access issues could be improved by agencies providing more information on and promotion of public access, such as signage or directions on websites.

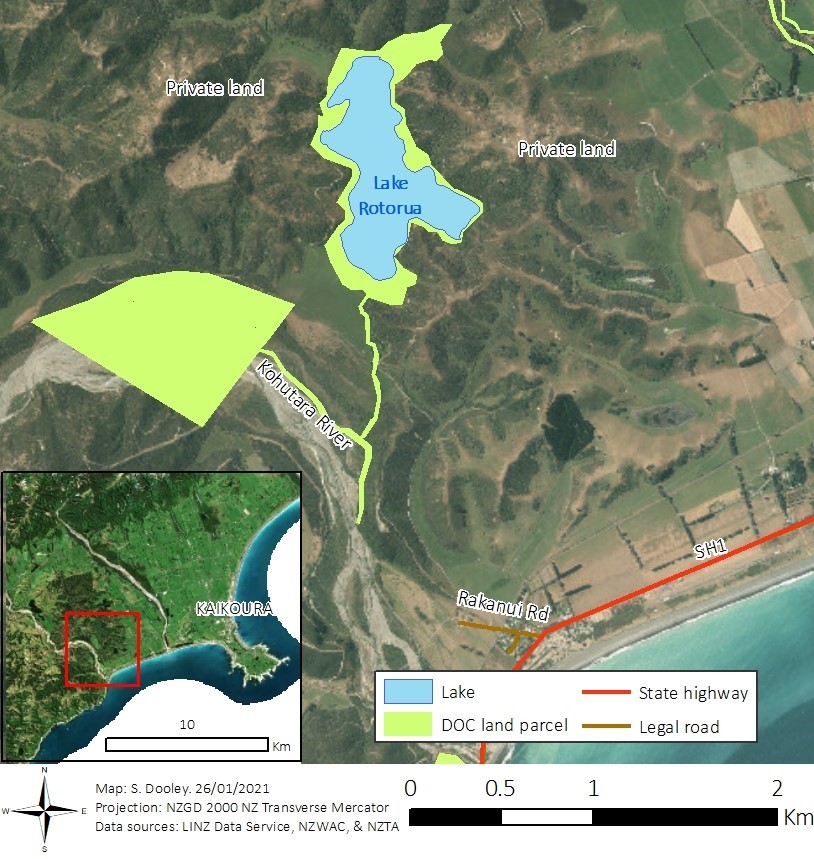

Other lakes would require significantly more work to establish access. Several lakes are isolated on private land. Lake Rotorua in Canterbury is one example. Legal access to the lake involves walking up a riverbed. Alternatively, the landowner could grant individuals access via a private farm track, but tracking down the contact details of the landowner to request their permission could be difficult.

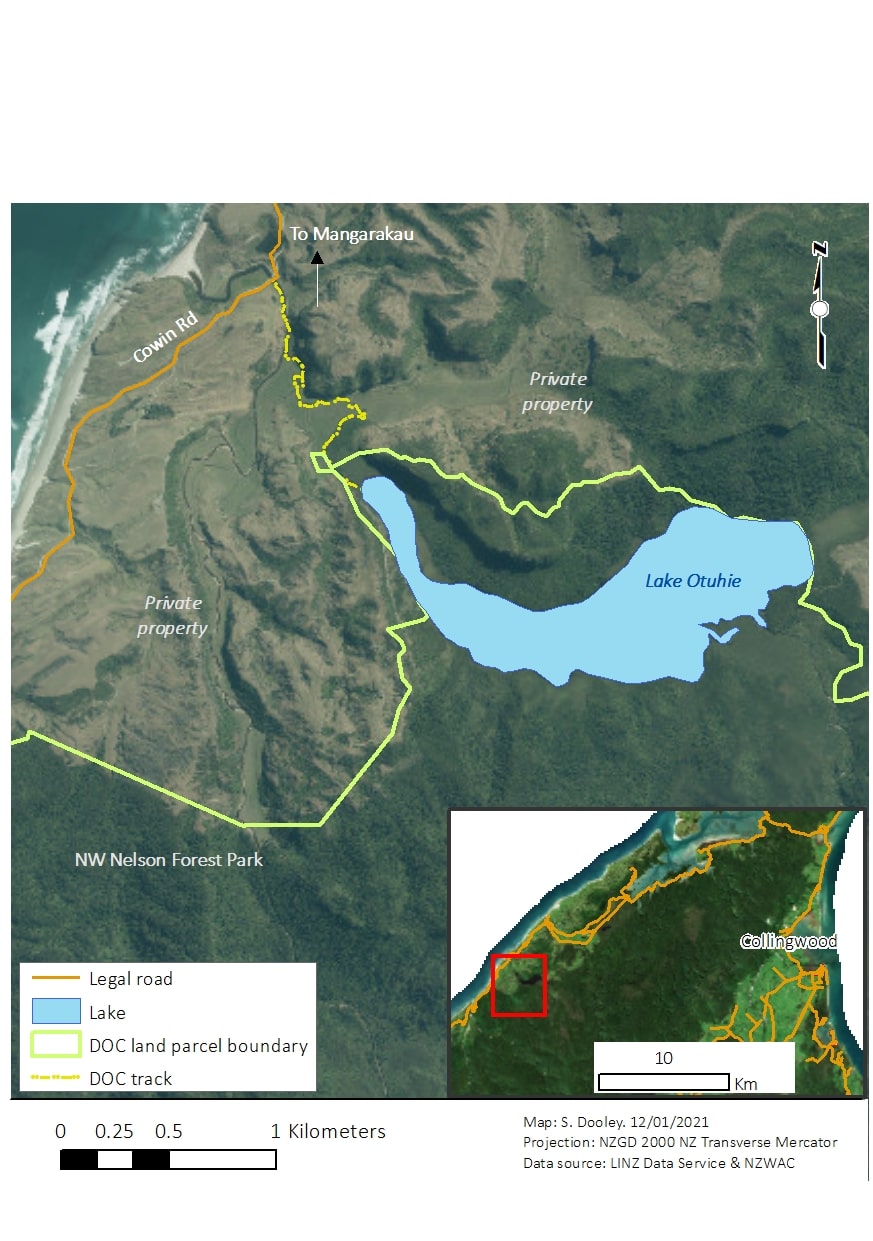

Another barrier to access is the terrain that lakes are located in. Many lakes are in remote locations accessible only by a 4WD vehicle or multiple days of tramping, requiring enhanced navigational skills. Lake Otuhie, in a remote corner of Tasman, for instance, is accessible via a short walk after a long drive possibly requiring a 4WD vehicle.

In determining public access to lakes, a major question I considered was why is access important? Should the public have access to lakes?

In contemplating access, I have realised that public access does not imply unrestricted access. There could be times, for instance, when access should be prohibited – for example, a Rahui/temporary ban can be used to restore health, allow recovery, or for cultural reasons. Yet, if access is accompanied by education and knowledge, I think most members of the public will do the right thing.

There is a greater risk that if New Zealanders lose access to lakes, critical connections and values will be lost or degraded. Declines in the environmental quality of lakes could go unchecked if the public is unaware of their existence.

Improved public access creates more opportunity for people to work together to ensure lakes are treasured for current and future generations.

As part of my project, I created an ArcGIS StoryMap summarising my results and further discussing public access and values. You can view it here:

https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/b511804c79d04a8b98381c96b2e7a798

A map showing the project results can also be explored here:

https://cawthron.maps.arcgis.com/apps/View/index.html?appid=37bdd1604a544607a71bb8cd37d887a4

Thanks to the Cawthron Institute and Lakes380 for this opportunity!